|

|

|

|

|

The real story

At age 31, he was still a single man, working as a blacksmith at the nearby town of Barczyzna, when he decided to emigrate to Australia. Some 16 years earlier, in 1838, a group of German Lutherans from the eastern Prussian provinces of Silesia and Posen had travelled to South Australia seeking freedom to practice their religion as they wished 1. The new settlers were offered land by George Fife Angas, a director of the South Australia Company, and soon prospered. Letters sent back to Germany spoke highly of life in the Antipodes and other settlers from Germany joined them. The South Australian government, impressed by the hard-working German immigrants, also encouraged further settlement by publishing information about the colony in Germany. News of a the settlers obviously reached Barczyzna, for Ludwig, Johann Menzel (33 years old), the Zadow family (Johann 47, Anna 38, Wilhelm 9, Emilie 7, Ludwig 5 and Justine 2) and Anna Freyer (a 60 year-old widow) decided to leave a Europe doggged by wars and cholera epidemics for the promise of a better life. They would have travelled by land and riverboat to the port of Hamburg, where, on 25 August 1855, they set sail on the “Steinwaerder”, a 258 tonne barque under the command of Captain Ahrens, along with 98 other passengers from different parts of Germany. The voyage to Australia was no cruise in those days; 17 weeks cramped in the steerage quarters of a small wooden vessel with limited rations2 and seasickness and scurvy as a companion. Two oil lanterns provided all the illumination for the steerage passengers. The ship docked in Port Adelaide on 19 December 1855. The heat of a South Australian summer that would have greeted him must have been a shock for someone who had spent his life in northern Europe. |

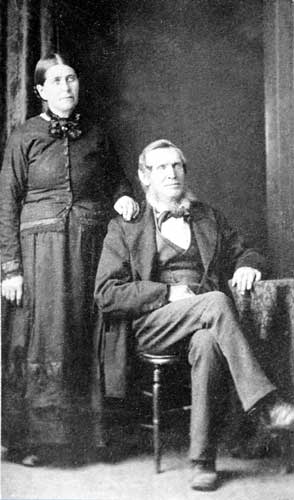

Ludwig moved about quite a bit during his first 11 years in Australia. He first went to the Barossa Valley, where other Germans had settled, working for the first few years as a carpenter. Records show that he bought 20 acres in Bethany from Carl Pohlner for £100 in July 1858 and then resold it eight months later for £200 – a tidy profit in those days. Here he met Dorothea Bartsch, daughter of Wendish immigrants from Saxony, Adam and Dorothea Bartsch, whom he married in 1859. The Bartsch family had arrived in Australia in 1848 and lived at Neukirch. According to his wedding certificate, this was also the home of Johann Ludwig Briese at that time. Interestingly, Ludwig and Dorothea were married in the Wesleyan Chapel at Gawler, some distance from Neukirch, on 16 September 1859. The mystery of why two German-speaking Lutherans married in a distant English-speaking church rather than the newly built Lutheran church in their home town is probably explained by the birth record of their first child, some four months later in January 1860. It is not clear whether it was their choice or whether the Lutheran Church refused to marry them; people were much less tolerant then, regardless of creed. Shortly after, they moved to the Eden Valley area, north-east of Adelaide, where Ludwig leased a small land holding and grew wheat. Four children, Anna Juliane (1860) and Auguste Louise Johanne (1861), baptised in the nearby Black Springs (now Springton) Lutheran Church, and two, Friedrich Wilhelm (1863) and Christiane Emilie (1865) in the new Lutheran church at Eden Valley. St Petri’s Church in was built in 1862 and it is likely that the family changed to a closer church rather than the place they lived. In fact, Ludwig is recorded as being a founding trustee of St Petri’s. |

Ludwig and Dorothea Briese (nee Bartsch) |

Insecurity of land tenure and decreasing soil fertility led the farmers of the region to look further afield. Virtually all the good land had been bought up by wealthy proprietors who then leased it at a high rents3. In New South Wales, under the Robertson Land Act of 1861, land was being allocated to new settlers for £1 per acre (with a 5 shillings deposit and three years to pay). Some of the men, including J.G. Scholz, checked out the possibilities in the Albury area of New South Wales and were pleased with what they found. Scholz and his family moved there and took up land in the Dight’s Forest (Jindera) area in May 1866.

Later that same year, the Brieses joined a group of German farmers (including J. G. Briese, C. Graske, J. Heincke, A. Heppner, J.G. Kalms, M. Klose, A. Koehn, W. Leicht, C. Mangelsdorf, J.C. Mangelsdorf, M. Matuschka, C. Neideck and L. Neideck) from the South Rhine District, including his parents-in-law and their family, to trek for some six weeks and 800 km by bullock wagon eastward along the Murray River corridor to Albury. The men first investigated land on the Victorian side of the river, as Melbourne was the closest market for farm produce and customs duties were charged for any produce that crossed the border between New South Wales and Victoria. However, on January 12 1867 the colonies signed a free trade agreement and the tariff barrier no longer applied4. The German settlers quickly took up their preferred land at Jindera, 15km north of Albury in New South Wales. Ludwig selected Lot 116 (320 acres) between Jindera Gap and the planned village of Jindera (Conditional Purchase 67.203 registered on 30 January 1867), and that same year purchased an additional 200 acres adjacent to it (Lot 160 – CP67.2050) in the name of his son, Friedrich Wilhelm. He was 44 years old and had finally found the place to settle down for the rest of his life. On 7 February 1867, Ludwig Briese became a citizen of the colony New South Wales. He set about building a home from clay bricks made on the property5 and clearing the land. The German settlers lost no time in improving their holdings and, within six months, had cleared and fenced land to sow wheat crops, as well as building houses and planned a church and school (see 100 years: Jindera New South Wales 1868-1968). Other groups of German Lutherans, including Ludwig’s in-laws the Bartsch family, soon joined these pioneers6, taking up land between 1867 and 1872. Sadly, shortly after arriving in Jindera, their second child, Auguste, died in May 1867. She was the first person to be buried in Jindera and her headstone is still near the site where the family house used to stand. Their Lutheran religion was very important to the new German settlers and they quickly formed a congregation. Initially services were conducted by the Elders, including J.L. Briese. The death of Auguste prompted the German settlers to call a minister who arrived in 1868. Services were initially conducted from a bush hut, situated next to the current St John’s cemetery until a wooden church, Bethlehem, was built nearby in 1872. Religion both drew the community together and split it apart, for the Jindera congregation soon found itself arguing about religious practices and the German settlers split into two factions. The Briese family joined with the group that aligned with the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Australia. As a consequence, in 1880, a second Lutheran church, St John’s, was built in Jindera village from bricks made on Ludwig’s property and to plans drawn up by Ludwig. This split persisted until 1966 when the two branches reunited. In the meanwhile, Ludwig farmed his land. Within a few months of arrival, the settlers had formed a Farmer’s Association designed to get market information and coordinate production7. Their new life in Jindera was rapidly underway. By 1875, Jindera was described as a “thriving small township with a number of substantial brick dwellings, shops and public houses, and a post office, with a farming community of some 350 persons, almost entirely of natives of north-east Germany, where nothing but wheat is grown. The farmers appear in prosperous condition and, year by year, increase the area of their holdings.” Clearly, wheat was the important cash crop in the early years, but the farmers also planted fruit trees, had large vegetable gardens and kept livestock for farm work and to produce meat and milk. Over the years, there would have been a gradual diversification from mainly wheat to the mixed cropping/meat/wool farming that occurs in the region today.

As their farming enterprise established and expanded, Ludwig and Dorothea had four more children, Anna Johanne Emma (1867), Hermine Bertha (1870), Johann Gottlieb Ludwig (1873) and Theodor Ernst August (1875). In 1882, Ludwig purchased the neighbouring “Springhurst” property from Richard Guest. He was now a successful farmer and watched his children grow up, marry and establish their own lives and, in some cases, shift to other parts of Australia. In his retirement, he lived on “Springhurst” with the family of his daughter Emilie and her husband, Albert Briese. During his life, he had moved to a different continent to establish a new life and, in the process, helped establish new communities in both South Australia and New South Wales. His origins may have been different from the legend but these achievements are a legacy to his descendants, who now number more than 1000. Ludwig died at his home in Jindera on 1 January 1911, aged 87, and is buried in St John’s Lutheran Church cemetery in Jindera. |

Footnotes 1 In 1817, the King of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm III, at that time, attempted to force a union between the Lutheran and Reformed Churches, believing that a single protestant church would strengthen the Prussian state. He also tried to impose a new Order of Service or “Agende” on this church, which he had largely written himself. Many Lutheran congregations and ministers resisted these moves, as they did not accept the new order of service. They also insisted on separation of church and state and did not accept the king as head of the new church. An appeal by the Lutherans in 1934 for freedom of religion led to further suppression, fines, imprisonment and confiscation of property. Congregations were forced “underground” and the seeds of emigration to escape religious persecution were sown. 2 The ship’s menu comprised one main meal per day. Each person received a daily bottle of drinking water plus the following: 3 The “South Australian Chronicle” in 1867 reported that “numbers of our most valuable colonists are leaving us, owing to the superior attractions of free selection in adjacent colonies.” The article further stated that about 80 families had settled in the Albury district where they “could get land there without delay and uncertainty, the competition of large capitalists and the intervention of land agents”. 4 The “Border Post” 30 January 1867 reported that “To show the probable effect upon the land revenue of the initiation of free trade across the Murray we may mention that, during the eight or nine days since it has become known that the two governments had signed a treaty to abolish the duties, twenty-six free settlers have taken up 5838 acres of land at the Albury Land Office. Before this period there were only one or two selections of limited extent per week. Most of the recent purchases were made by German families just arrived from Adelaide. There were thirty-nine of these families who came overland with their wagons, their stock, their capital and their household goods. They were at first doubtful whether they would settle on the New South Wales side of the border and procured plans of the agricultural areas open in the neighbourhood of Beechworth and Chiltern, in Victoria. The news of the abolition of the customs, however, would seem to have fixed them in a determination to settle on the north side of the border.” 5 The clay must have been of good quality, as Boral Bricks now have a commercial plant at this site. 6 The “Border Post” 8 May 1867 reported that “The exodus of German farmers from Adelaide to the Upper Murray is on the increase. We are informed that 79 families from Mount Gambier and elsewhere have already arrived in Albury, and that fully 800 families may be expected in all. These people are mostly tenant farms who have the habit of renting farms near Adelaide, at from £8 an acre downwards. On the expiry of their leases they naturally turn their attention to a locality where good soil is to be purchased conditionally at £1 per acre, with plenty of time to pay the purchase price. Of course this immigration tells upon the receipts of the Albury Land Office. Last Thursday 1775 acres were taken up and, if this rate of procedure is maintained, the old estimate of a sale of 1000 acres per week will have to be altered. The new arrivals from Adelaide are of very superior class. They appear to have plenty of capital, and they bring with them their own teams, wagons, and sometimes farming implements. All those we have conversed with have acquired plenty of colonial experience and speak English fluently. Each family, as it settles down, communicates the results of its experience to former neighbours in south Australia and this correspondence forms a capital advertisement for this district. We have no means of judging whether the estimate of 800 families intending to settle amongst us is correct, but if so, the population of Albury will be doubled within a twelve month period.” 7 The “Border Post” 3 April 1867 reported that “The newly arrived Germans from Adelaide are endeavouring to form a farmers’ club at Albury similar to the ones they had been accustomed to in South Australia. They pay a small annual subscription, which enables them to receive daily telegrams concerning the price of wheat in such markets as may be available to them. Members of the club occasionally favour their brother farmers by recounting their individual experiences and the information thus collected is always more or less valuable. A secretary who receives £30 a year is the only officer required, and the qualification of the membership is much lower than the value of the information received.” |

This site powered by The Next Generation of Genealogy Sitebuilding ©, written by Darrin Lythgoe 2001-2024.